Costa Rica is such a mountainous country. It’s quite the change from where I hail from. Even though I’ve lived in Costa Rica for several years, the uplifted scenery is still sort of unbelievable.

In Western New York, the nearest biggest ranges gently slope their way up to 2,000 feet. As I write this, I’m at least a 1,000 feet higher and yet, that’s still low for Costa Rica! Let me tell you, around here, there’s some serious topography going on.

The middle of the country is a blend of volcanic and tectonic lands that push into the sky. Rivers and streams descend through canyons and pour into hot lowlands replete with parrots, macaws, and other tropical diversity. The average landscape makes for slow, winding drives but the scenery is pretty darn special.

The birds make up for slow drives too! If it weren’t for all of these mountains, we wouldn’t have nearly as many bird species in Costa Rica. The big hills are natural walls that simultaneously collect and block rain, stop dispersal, and create other circumstances for distinct habitats. Each of those habitats have their birds including one of the most special; high elevation forest.

By high elevations I mean lands more or less above 1,800 meters. That point is about where birders start to see the birds of the high, cool weather places, birds you’ll want to see because most of them are sweet endemics.

In the mountains of Costa Rica and Panama, we have 60 to 63 endemic bird species along with several endemic subspecies (maybe some will be changed to species level taxa). Of those birds, 20 or so only live in high elevations areas.

That’s like having more than 60 bird species that only live in the mountains of West Virginia or Wales.

Yeah, imagine how crazy that would be! Such happy avian craziness comes true in Costa Rica.

To see most of the high elevation species, you’ll have to visit one of four main areas. Here’s a run-down and what to expect from birding in those places. In case you wondering, I’ll just mention now that quetzals are equally fairly easy to see in all of these areas (in suitable habitat of course).

Poas Volcano

Given its proximity to the San Jose area, Poas has the quickest and easiest access to high elevation habitats. Just drive 40 minutes up a main, nicely paved road from Alajuela and you’ll get there!

Some other advantages

- Easy roadside birding on the way to Poas National Park.

- Easy to combined with roadside birding in middle elevation habitats.

- Especially good for silky-flycatchers and Fiery-throated Hummingbird.

- Plenty of restaurants and cafes.

- Perfect choice for a quick morning or day trip, especially from the Alajuela area.

Some disadvantages

- Not as much high elevation forest as other areas.

- If the road to the volcano gets closed, there is very limited or no real access to elevations above 2,000 meters. On rare occasion, this can happen!

- Lacks Timberline Wren, Volcano Junco, Sulphur-winged Parakeet, Silvery-throated Jay, and Ochraceous Pewee.

- Usually busy on weekends.

Barva Volcano

No many people go birding at Barva Volcano. There’s a ranger station and great forest but access is not as easy as other spots.

Some other advantages

- Good trails in excellent high elevation forest with expected excellent birding. Might be a good spot for Highland Tinamou.

- A good choice for birders looking to avoid crowds.

- Little birded (for those in search of personal discovery).

Some disadvantages

- You have to drive up a narrow road also used by over-sized milk trucks.

- You have to park your vehicle and hike uphill for at least two kilometers.

- Trails are only accessed from the ranger station and that doesn’t open until 8. You probably also need to buy your tickets online and in advance.

- Very few dining options, maybe one or two where you leave your car.

- Like Poas, Barva also lacks Timberline Wren, Volcano Junco, Sulphur-winged Parakeet, Silvery-throated Jay, and Ochraceous Pewee.

Irazu and Turrialba Volcanoes

I grouped these two volcanoes together because they are right next to each other. They mark the closest spot to San Jose that goes above the treeline. Irazu in particular has a nice, paved road all the way up to 11,000 feet!

Some other advantages

- Easy access on good roads for Irazu.

- Some good roadside habitat, especially in the Nochebuena restaurant area.

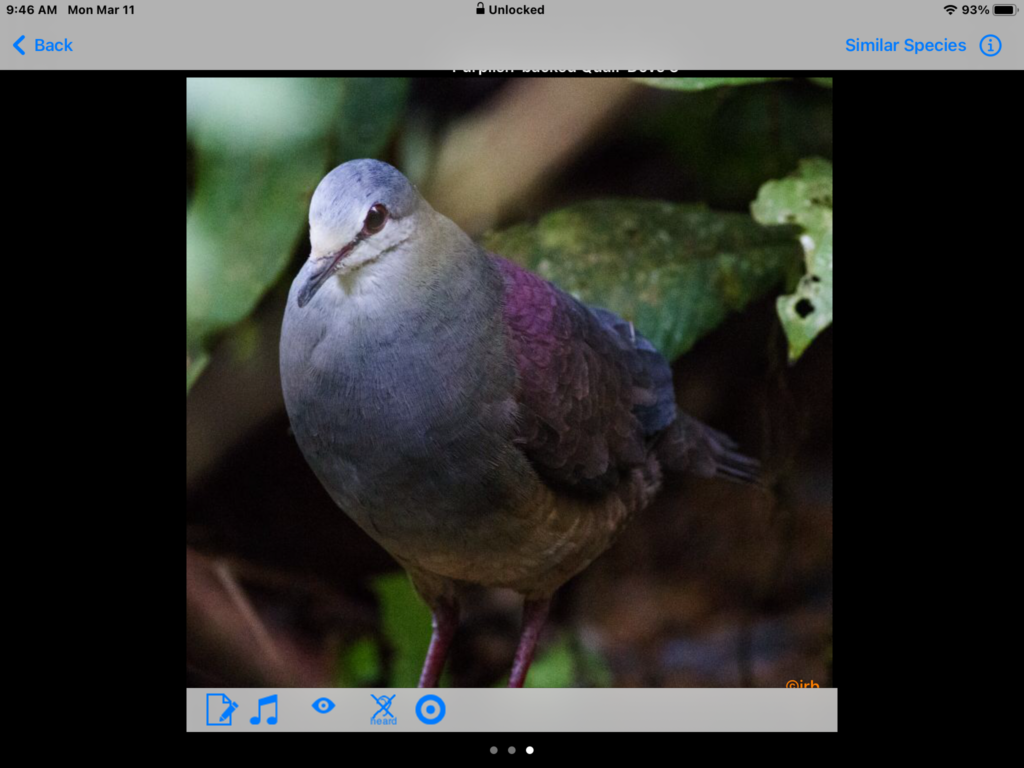

- Reliable site for the mega Maroon-chested Ground-Dove. It might be “easier” here than anywhere else in the world.

- High enough for chances at Unspotted Saw-whet Owl, and a good area for Volcano Junco and Timberline Wren.

Some disadvantages

- Rough roads to Turrialba.

- Often busy on weekends and holidays.

- Rather limited access to extensive intact forest.

- Silver-throated Jays and Ochraceous Pewees are very rare and local, and there aren’t any Sulphur-winged Parakeets.

Cerro de la Muerte and the high Talamancas

This is the main high elevation area most tours and birders visit and with good reason. The Talamancas have the largest areas of intact high elevation forest, and chances at seeing all high elevation specialties.

Even so, the area still has its own ups and downs.

Some other advantages

- Lots of great habitat to explore. There are several sites and roads that access excellent habitat.

- Easy access to Timberline Wren and Volcano Junco.

- Best chances at the jay and pewee (although they are still tough!).

- Chances at Unspotted Saw-whet Owl.

- Several lodging and dining options, especially in the Dota valley.

Some disadvantages

- The main access road is good but landslides can affect some parts during the wet season.

- Not very suitable as a day trip from San Jose. It’s possible but would involve a lot of driving time.

These are the four, principal high elevation areas for birding in Costa Rica. If you have more time, staying in the Talamancas is worth it. However, since some species seem easier at Irazu and Poas, it’s worth spending a day at one or both of these other sites too!

Want to learn more about where to go birding in Costa Rica? Support this blog by getting “How to See, Find, and Identify Birds in Costa Rica” ; a 900 plus page birding site guide for Costa Rica. Start planning your birding trip to Costa Rica now, I hope to see you here!