Quail-doves seem to herald from the realm of birding dreams. The plump birds aren’t quails but you could be excused for believing it. They are indeed doves but are a far cry from those everyday, easy-peasy Mournings.

Instead of sitting in the open or easing on down the middle of a road, quail-doves lurk in the shadows. Shy by nature, quail-doves are careful. I can’t blame them. I mean if I had to walk the same forest floor as hungry Ocelots, boas, and other animals that couldn’t wait to devour me, I’d be pretty darn timid too!

Most forest floor birds are careful but quail-doves take it to another level of caution. They have to because unlike somberly plumaged wrens, antbirds, and Swainson’s Warblers, quail-doves are downright fancy.

They got cool little face patterns and patches of iridescence that transform them into beautiful little birds. Quail-doves can still sort of blend in but not if they take bold steps, and definitely not in open habitats.

All of that cautious behavior makes quail-doves somewhat more challenging to see than other birds. You can still find them, sightings can happen (!) but only if you get lucky, or play by quail-dove rules.

Those would be:

- Walking slow and careful like a quail-dove.

- Keeping silence. Forget talking, better to not even whisper.

- Keep an eye on the forest floor in mature forest, especially below fruiting trees.

- Listen for and track down calling quail-doves.

Yeah, that’s especially challenging in group birding situations and requires a high degree of patience but what are you gonna do? Thems are the quail-doves rules!

Now that you have a fair idea of how to look for quail-doves, here’s some tips to identify them in Costa Rica. The two main problematic species are the first ones mentioned, I’ll mostly focus on them.

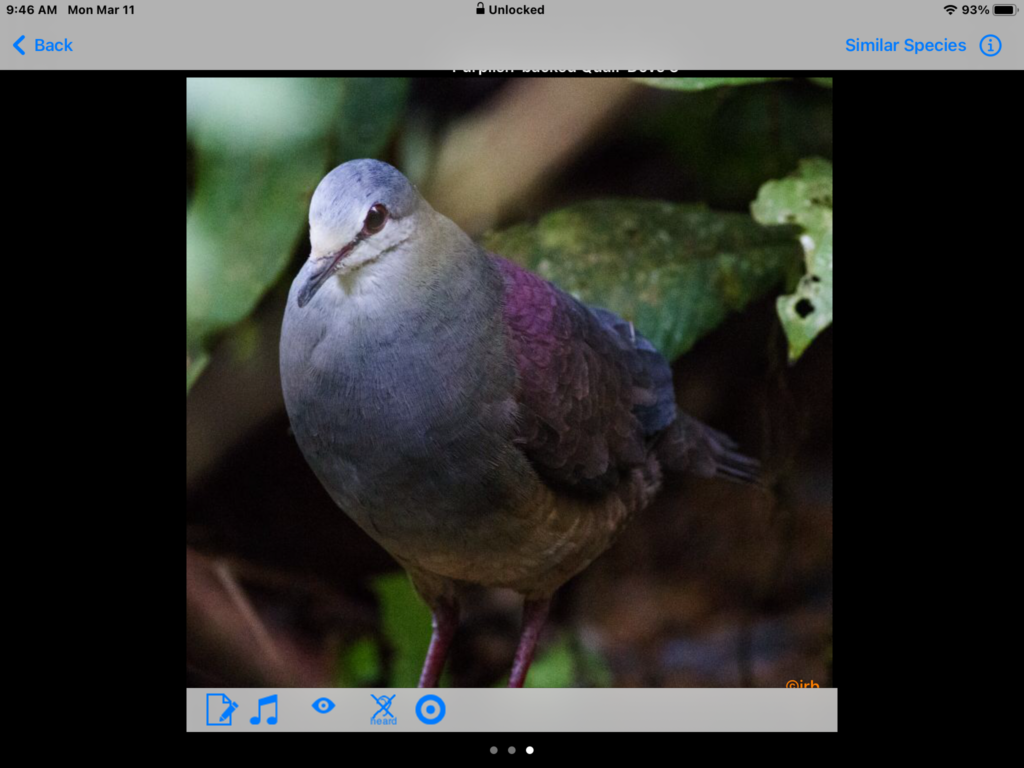

Buff-fronted Quail-Dove vs. Purplish-backed Quail-Dove

Way back when, in more ecologically healthy times, ancestors of these two species took two different paths. One preferred the high road, and the other, the not so high road. After long years of separation, one became the Buff-fronted and the other the Purplish-backed.

Despite their names, these two species can look a lot more similar than you think, especially when they give you typical, few second, quail-dove views The heavily shaded, understory conditions don’t help either!

Both have a similarly patterned, mostly gray head, dark back, and gray underparts. If you know what to look for, separating the two isn’t all that problematic. Confusion stems from the color of the back, and expecting to only see Buff-fronteds at high elevations.

Regarding their back, the Buff-fronted’s is maroon-brown, maybe with a hint of burgundy; a color that can easily make you wonder if it might actually be some shade of purple. Focus on that tint, especially if the quail-dove is in middle elevation cloud forest, and it’s easy to enter it into eBird as a Purplish-backed.

If you see a quail-dove like this at high elevations, yes, without a doubt, Buff-fronted. Purplish-backeds only typically range up to around 1,200 meters or so. But what about the adventurous Purplish-backeds that walk a bit higher? What about Buff-fronteds that commonly range down to 1.200 meters or even lower?

Oh yeah, they can overlap! Buff-fronteds stroll at lower elevations than you think. Perhaps they are limited to old second growth in such elevations? Maybe other odd situations such as the feeders at Cinchona?

Whatever the case, you CAN see these two birds in the same area. That just means that in places where foothill rainforest transitions to cloud forest, you can’t assume identification based on elevation.

Instead, if you see a quail-dove at Cinchona or other spot with similar elevation, focus on these main field marks:

- See if the bird has a buff or just pale gray front- The Buff-fronted lives up to its name. The Purplish-backed has a pale gray front.

- Look at the back- If the bird has a green nape, and the back and wings are the same maroon-brown color, it’s a Buff-fronted. If the bird has a distinct amethyst purple patch on its back that contrasts with duller brown wings, hello Purplish-backed!

Ruddy Quail-Dove vs. Violaceous Quail-Dove vs. White-tipped Dove

In general, these are pretty easy. Both Ruddy and the rare Violaceous have reddish beaks but Ruddy is more brownish or red-brown with pattern on its head while Violaceous has a more uniform grayish head and contrasting white underparts.

Based on its general plumage pattern, the Violaceous might remind you of a White-tipped Dove. However, if that “White-tipped” has a red beak , grayish head, and rufous tail, it’s a Violaceous Quail-Dove.

Chiriqui Quail-Dove

This hefty quail-dove is pretty easy. No other quail-dove in Costa Rica is brown with a gray cap.

Olive-backed Quail-Dove

Another easy quail-dove, at least to identify. It’s the only one that has mostly dark gray plumage and a white mark on its face.

Quail-doves are some of the tougher birds to see in Costa Rica. They require a special type of patience and can be especially tough on group birding tours. However, play by their rules and you can see them!

Maybe not the Violaceous but if you go to the right places, the other quail-doves for sure! Learn more about seeing quail-doves and other birds in Costa Rica with “How to See, Find, and Identify Birds in Costa Rica”. Use it to get ready for your birding trip to Costa Rica and see hundreds of bird species. I hope to see you here!